If it sounds like a horror movie, we should not be surprised, for it is a scenario bound up into our very concept of horror. The infected creature now has only days to live, and these he will likely spend on the attack, foaming at the mouth, chasing and lunging and biting in the throes of madness - because the demon that possesses him seeks more hosts. Aggression rises to fever pitch inhibitions melt away salivation increases. Once inside the brain, the virus works slowly, diligently, fatally to warp the mind, suppressing the rational and stimulating the animal. Instead, like almost no other virus known to science, rabies sets its course through the nervous system, creeping upstream at one or two centimeters per day (on average) through the axoplasm, the transmission lines that conduct electrical impulses to and from the brain. On entering a living thing, it eschews the bloodstream, the default route of nearly all viruses but a path heavily guarded by immuno-protective sentries. Fittingly, the rabies virus is shaped like a bullet: a cylindrical shell of glycoproteins and lipids that carries, in its rounded tip, a malevolent payload of helical RNA. It is the most fatal virus in the world, a pathogen that kills nearly 100 percent of its hosts in most species, including humans.

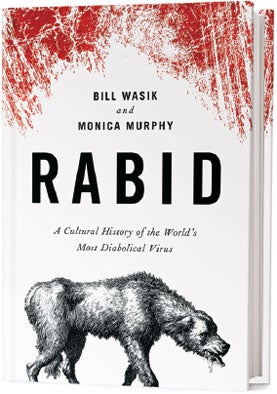

In Rabid: A Cultural History of the World’s Most Diabolical Virus ( public library), Wired senior editor Bill Wasik and veterinarian Monica Murphy, a husband-and-wife duo, trace the fascinating history of the ubiquitous and menacing virus that shaped everything from the Holy Crusades to modern zombie and vampire pop-culture mythology. But what happens when a microscopic particle enters the body, takes hold of the mind, and gnaws away that access to our own consciousness? Is what remains “human”?

Our understanding of what it means to be human hinges on an understanding of consciousness and, perhaps more than anything, a sense of control over or, at the very least, access to it.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)